I picked Wild Turkeys for my first blog post because they are a bright spot in a often dismal overview of species decline. Turkeys are thriving after nearly going extinct in the 30s. Most of the time when turkeys are seen, they shyly melt into the undergrowth. But a few become acclimated to humans, and are easy to observe. They are fast runners, up to 25 mph. They are also excellent flyers (up to 55 mph), a surprise for such a large bird, but perhaps not so surprising when one considers that they roost high in trees at night to escape predators such as coyotes, cougars, foxes, bobcats, and of course humans. Many, besides the original Pilgrims, consider wild turkey dinners a treat.

Belying their size, turkeys are good fliers.

They are native to North and Central America. Five subspecies are recognized. Our local species is Merriam’s, which ranges from southern Mexico into Colorado.They especially like Ponderosa Pine seeds and the fruit and leaves of Kinnikinnic, a low ground cover growing under pines, as well as grubs and other insects they scratch up with their powerful feet.

Most waking hours are spent searching for food.

Recent forest fires have opened a patchwork of burned and untouched areas. Turkeys like this type of ground cover because seeds and insects are easier to find on scorched earth, while the natural forested areas provide shelter from winter winds, roosting trees and refuge from predators.

Turkey roosting against smoke filled sky.

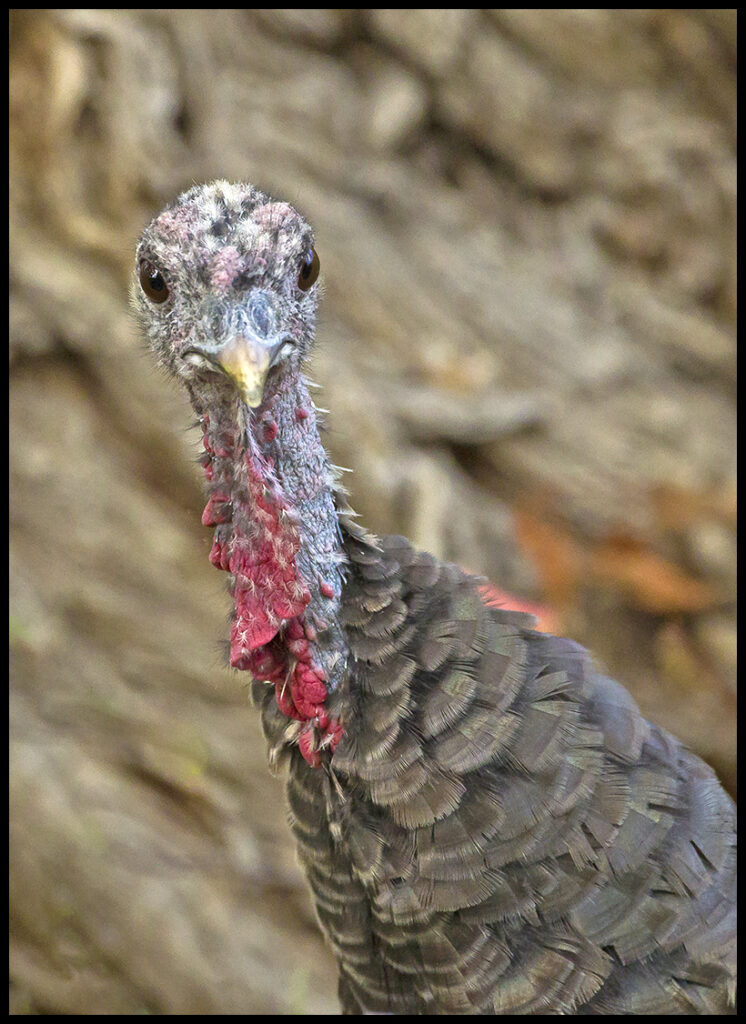

In spring, the toms (males) strut their stuff before the hens (females). In their breeding plumage of gorgeous iridescent golds, greens, coppers, and bronze, they spread their huge tails, puff up their feathers, and pose so their naked head and neck of blue, plus red wattles and fleshy red snood hanging from the beak all are in full view. Then with all the dignity they can muster, they turn slowly so the hens will be suitably impressed. However, until the hens are ready, they fain indifference. Breeding toms gobble loudly…a sound that carries up and down the valley. The rest of the year, the whole flock mutters softly among themselves.

Beautiful turkey feathers. They have a lot to keep them warm during the winter months. Turkeys don’t migrate.

Females lay 9 to 14 eggs in a nest scraped out under bushes or in tall grass. She lays about 1 a day and only starts sitting after all are laid so that all will hatch at the same time. She incubates for 28 days. At the end of this time they all leave the nest. Poults (newly hatched babies) are precocial, meaning they can feed themselves as soon as they hatch. Obviously the eggs and poults are vulnerable to predation during this time. Besides the culprits listed above that happily eat adults, she also has to worry about owls, raccoons, possums, skunks, foxes, raptors, bears, and snakes raiding the nest or attacking the young. The survival rate for juveniles is low, but there are enough of them that their numbers keep increasing. Life expectancy is 2 to 3 years for adults.

Turkey poult. Notice the egg tooth at the end of the bill. It’s used to help crack the shell so the little one can get out. The egg tooth will drop off as the poult ages. This little fellow took an unplanned bath.

Young turkeys can fly at 2 to 3 weeks old.

Survival rate for young turkeys is dismal, but they are thriving nonetheless.

The juveniles stick close to mother until they are adults.

I like having wild turkeys around even though they can do damage to gardens and yards in their search for food. They are fun to watch.

Faces only a mother could love.

See and hear the turkeys by clicking this link. turkeys on parade

I’m adding a photo of our turkey’s tropical cousin from the Yucatan Peninsula, only because these are the most stunning turkeys I’ve ever seen. This is a female, the males have even wilder colors and head gear. They are endangered.

Ocellated Turkey (female) of the Yucatan Peninsula.