Hoatzin group – exciting new birds for me. Pronounced “What seen”

Note where the Cuyabeno area is in eastern Ecuador. We were on the eastern edge, near the Peruvian border. Most of the “Oriente” is covered by the Yasuni National Park and the Cuyabeno area administered by Kichwa Communities.

It was an inauspicious beginning. Mechanical trouble delays on the ground in Denver might have been overcome if they’d been able to get the plane door open in LA. Rescheduled…on a morning flight to Houston then Quito on the flight I’d tried to avoid because it got into Quito after midnight. We had to be back to the Quito airport early to catch the local flight to Coca where our 7-day trip to the Cuyabeno Reserve was to begin. Our luggage was still in LA. So, alas, no suitcase for a week in the jungle. We were met at the Coca airport by our group; three guides, a photographer from England, and George from Toronto. All good guys. We stopped briefly to pick up sun hats, bug bomb, and sunscreen plus a couple of shirts.

At the ferry stop we piled into a long, narrow dugout with all our supplies. All food and water has to be brought in as there are no shops out in the wilderness. Dugouts now are fiberglass covered wooden boats of the same dimensions as the original dugouts. No one uses real dugouts anymore because they are too heavy, expensive, and the trees are endangered. The afternoon was hot, humid, and threatening rain. In fact, it had rained most of the day on the way to the river. But miracle of miracles, it didn’t rain on us for the entire week. Once we left the small riverside town, we didn’t see more than a single other dugout per day.

River ferry. The size of this small Amazon River tributary, the Aguarico, gives an idea of the amount of water in the upper basin. This is only one of several nearby rivers.

Our first wildlife sighting happened before we even left the dock. Squirrel monkeys are the most visible monkeys in Ecuador.

And off we go to our first night’s accommodation. Rain clouds look menacing but failed to dump on us.

In 1979, the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve became the second largest reserve of the 56 national parks and protected areas in Ecuador. From east to west, the elevation gently slopes downward to the east within an area of 2,330 square miles. The area is a poorly drained plain with a watery network of forests, lagoons and creeks.

Watery world of the Cuyabeno

Such swampy conditions are rare so close to the Andes, where the drainage in the foothills normally prevents swamps and lakes from developing. By necessity, travel in the area is by boat. Most of the area is roadless, verdant jungle.

The shore was solid forest except for a few typical houses along the banks with the requisite dogs keeping watch.

On the edges of the rivers were glorious forests.

Along the wide river we saw an assortment of birds new to me.

Sand-colored Nighthawks. Usually crepuscular, these (with many more on the same logs) were out during the day.

Black Caracara

A four-hour trip downriver brought us to our first night’s lodging after dark. A real bed and ensuite bathroom.This was glamping.

The original Kichwa Lodge. The building on the left is a 3 bedroom guest house with plumbing, and the building on the right is the staff housing and kitchen.

There are other very upscale lodges closer to population centers on the Napo River which are owned by large Quito-based businesses, but this is the only eco-tour option in the Cuyabeno region owned and operated by a local indigenous community. Edgar Noteno has made it his life’s ambition to directly support the indigenous community which survives on subsistence farming and fishing and has limited employment opportunities. He wants to raise money to give some promising students the option for higher education with the hope they will return to help the whole community. Eco-tourism is the life blood of the area.

On rotting wood, a 3 inch centipede.

The guides woke us in the predawn darkness for our first day’s river cruise. The pleasant temperature and surprising lack of bugs, along with the dawn chorus made this regular morning event a favorite part of the day. Along the jungle banks we saw exotic birds, monkeys, etc.

Wattled Jacanas, adults

Wattled Jacana, juvenile

Cocoi Heron, similar to blue herons.

The Kichwa aren’t the only indigenous population in Ecuador’s Amazon, but it is the most populous. They are an ancient Andean tribe, with a strong connection to the forest and animals. There are over 400 organized communities consisting of a few families living in primitive, yet comfortable conditions. We stopped at a native community to see their turtle breeding program.

Sand bed with turtle nests. They know exactly when the baby turtles will hatch. They take the babies to lined ponds to raise them until they are big enough to release in the main river without too much fear of predation.

Baby turtles emerging.

This particular community has made it their mission to save and repopulate Amazonian River turtles. The turtles are an important animal both spiritually and economically. Due to commercial hunting and pollution the turtles were in trouble. In 1991 this community set out to save them. They are doing a great job, as along the river we saw hundreds of basking turtles.

Amazonian River turtles.

Surprise, surprise. We weren’t going back to our comfy lodge. We were heading for a place Edgar and his staff had recently built. After passing and acknowledging the Peruvian border guards at a station along the river we turned left and followed the border river to our new set-up.

Peruvian border way-outpost.

The rivers here are loaded with pink dolphins which you will never see doing this. Nearly every lodge in the area uses this internet photo to advertise the dolphins…but they rarely to never jump out of the water. You will only see them roll up to get air.

A dock below led to a boardwalk and then to a large platform on stilts with open sides and a thatched roof where we would set up our tents.

Unloading at our new digs.

Second lodge with tents on the deck.

Wait, tents? No beds? Hard wood floor? No way! I commandeered a couple of thick mattresses I found stacked near the staff quarters, to put under out tent. Much better. At the rear of the large platform was a primitive kitchen and a couple of tables. The raised boardwalk continued to a pair of stalls with a toilet and a shower that used water pumped from the river. The staff bathed in the river.

Layout of the second lodge.

This would be our home base for the next three nights. The area is a maze of channels, marshes and bays that are great for wildlife spotting.

Black-capped Donacobius pair

Amazonian Umbrellabird, Fem.

Riverside flower with two butterflies.

My biggest thrill was spotting many Hoatzins. These are very odd birds about the size of pheasants. While many birds eat insects, seeds, and fruits, the Hoatzin eat only plants, especially the leaves. Its digestive tract is adapted to a mostly vegetarian diet, in common with ruminants like cows. Because of this, it can give off an unpleasant fermenting smell. We didn’t get close enough to smell them.

Adult Hoatzin

It’s the only member of its genus, family, and order. These birds are the last representative of an avian lineage that dates back to the time of the dinosaurs. They are weak flyers and can be heard crashing through the foliage. Monkeys and raptors are their primary predators.

Young Hoatzins use claws on their wings to climb back to the nest should they leap out to avoid predators. They are good swimmers. The claws fall off in adulthood.

Evening on a black-water river. Who knows which river, there are so many.

Back out next morning with wonders to behold, only a fraction of which I have room to show.

Capped Heron

Blue-and-yellow Macaws

Giant river otter

Southern Lapwing. Notice the spur on its wing.

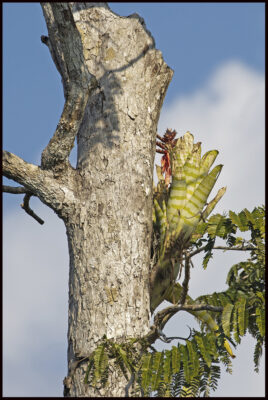

Bromiliads of all sizes and shapes grow in profusion.

Caiman lurk in the smaller, clearer waters.

White-eared Jacamar.

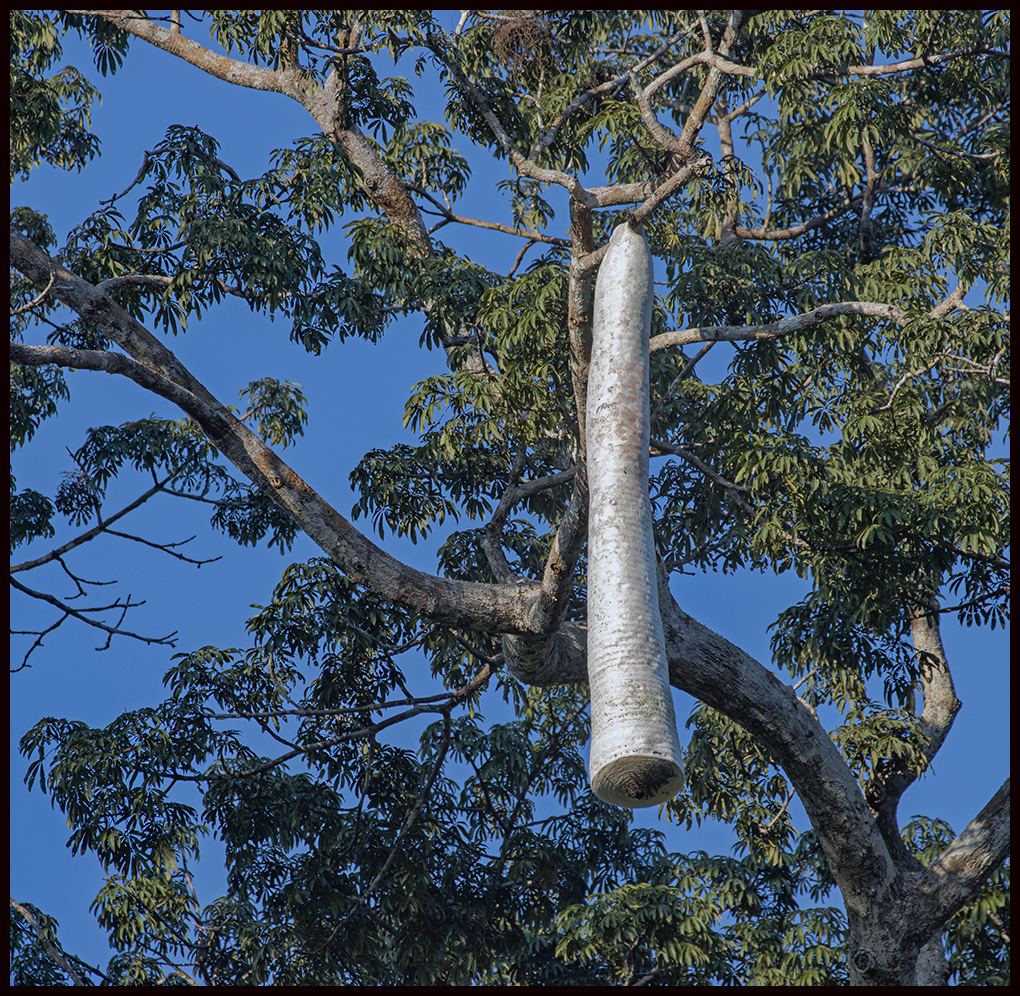

A two meter long wasp nest high in the canopy.

A termite nest; not nearly as exciting as the huge wasp nest.

Black Vulture pair.

And it being me writing this blog, dragonflies must be included. There were many species flying near our lodge.

Although we never saw a capybara on this trip, their tracks were everywhere. Spotting animals in the dense jungle is challenging.

A sunset follows our boat back to camp.

I’ll say good-bye for now until I get the next part together.