Gulf side gulls and pelican in food chase.

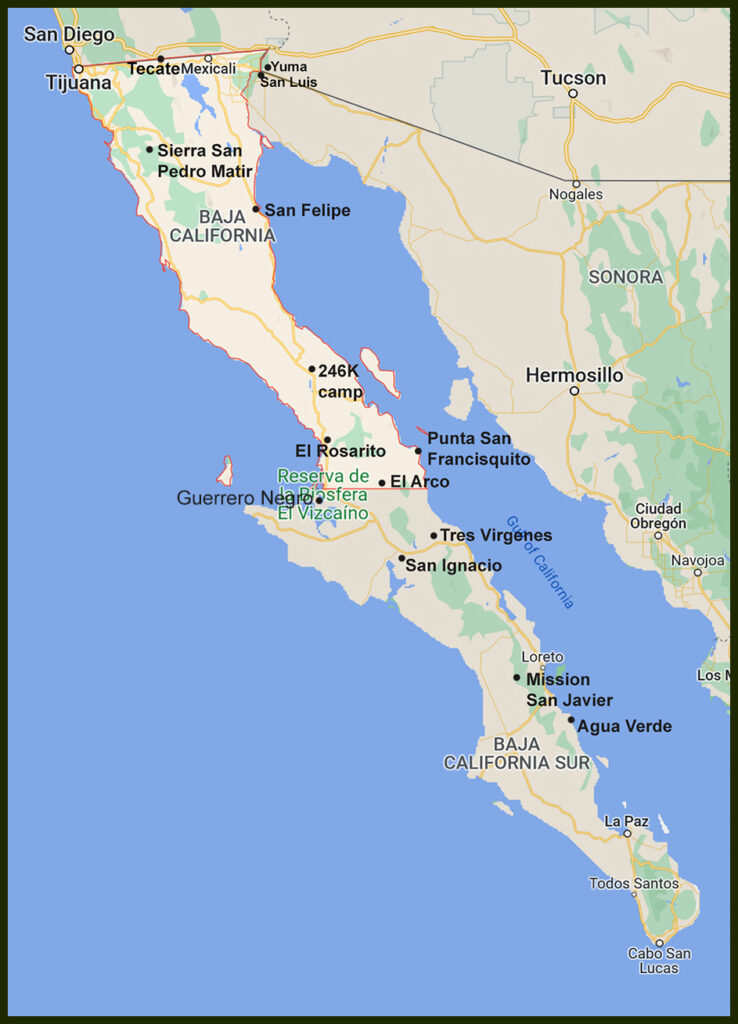

Continuation of the new and old interesting places in Baja.

Loreto was our planned southern extent for this winter. It’s a nice size colonial town with all the amenities one could need and the requisite picturesque town plaza. We wanted to revisit the inland Misión San Javier because the drive in is so lovely and the mission so well preserved.

From Wikipedia I learned the Jesuits of Loreto, one of the first established colonial towns on the Baja peninsula, were told by local Cochimi Indians of productive land in the nearby Sierra de la Giganta mountains. So, in 1699 a Jesuit priest with ten Spanish soldiers led by a dozen Cochimí guides, climbed into the mountains on horseback and entered the valley where the first mission was built. Efforts to grow crops failed due to lack of water so in 1710 the mission was abandoned and a new one built to the south at its present location which has a dependable source of spring water. The Jesuits and their Cochimí helpers constructed dams, aqueducts, and stone buildings. They planted date palms, olive trees, citrus and other crops. Between 1744 and 1758, the Mission San Francisco Javier was completed. It’s an oasis in the mountains supporting a small village surrounding the mission.

Misión San Francisco Javier

Restored interior

Food given out by the Jesuits initially drew the Cochimí to the mission, but over the longer term, the missionaries’ attempt to domesticate the Cochimí was the natives’ downfall. The proximity to Europeans spread disease, such as smallpox and measles. The diseases caused the native population to decline steadily. By the early 19th century, the Cochimí became extinct as a culture.

By 1817, the mission was deserted.

The church has been restored and is now maintained by Mexico’s Nat. Inst. of Anthropology and History.

Olive tree brought by the Jesuits is now around 325 years old.

Scenic drive into the mountains. Notice the date palms growing in the canyon. Loreto Bay is sort of visible in the distance.

When we visited a few years ago the rivers were flowing and birds abundant. Not this year. The drought strangling the whole southwest USA is a problem for Baja too. The river near the mission was nearly dry with small waterholes available for the cows and wildlife…a few fish and dragonflies!

Waterhole near the mission.

Fish surviving in one of the few waterholes left.

A number of different dragonfly and damselfly species flitted about.

Since we’d left late in the day for the mission, we stopped to camp before we got there at around the 8K mark in a valley we noticed that looked inviting. There we found a totally isolated campsite off the main valley that one wouldn’t want to camp in if any rain were in the forecast. There was a trickle of water coming in and a few waterholes above.

A secluded canyon that obviously floods on occasion.

Friendly, curious burros in the valley.

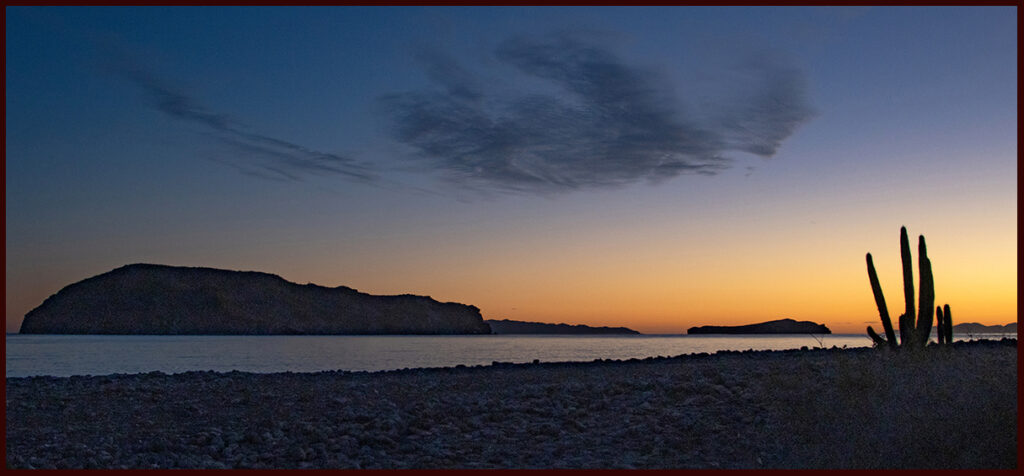

We’d planned to drive over the mountains to the west coast from the mission, but were discouraged by a report that most of it was open, boring (and now dry) ranchland on the other side…so we stayed a night at a favorite spot off the road to Puerto Agua Verde before turning north.

The road to Puerto Agua Verde with an arrow showing where we like to camp.

The very small town of Agua Verde has a small church and bodega. People who live there need the income from tourists, but the road is rough and we’ve never made it all the way. However, there is some reporting on the internet about what is available at the end. The beaches look lovely and very few campers make it that far. Some boats stop in the bay and fisherman like the area. For us, we love our favorite site on a rocky shore near a colorful lagoon.

Sierra de la Giganta meets the Gulf here.

The beach at sunrise.

View from the campsite.

Nearby lagoon supports a number of waterbirds.

Brown Pelican; landing gear down.

Brown boobies in large flocks plummet from on high to catch fish.

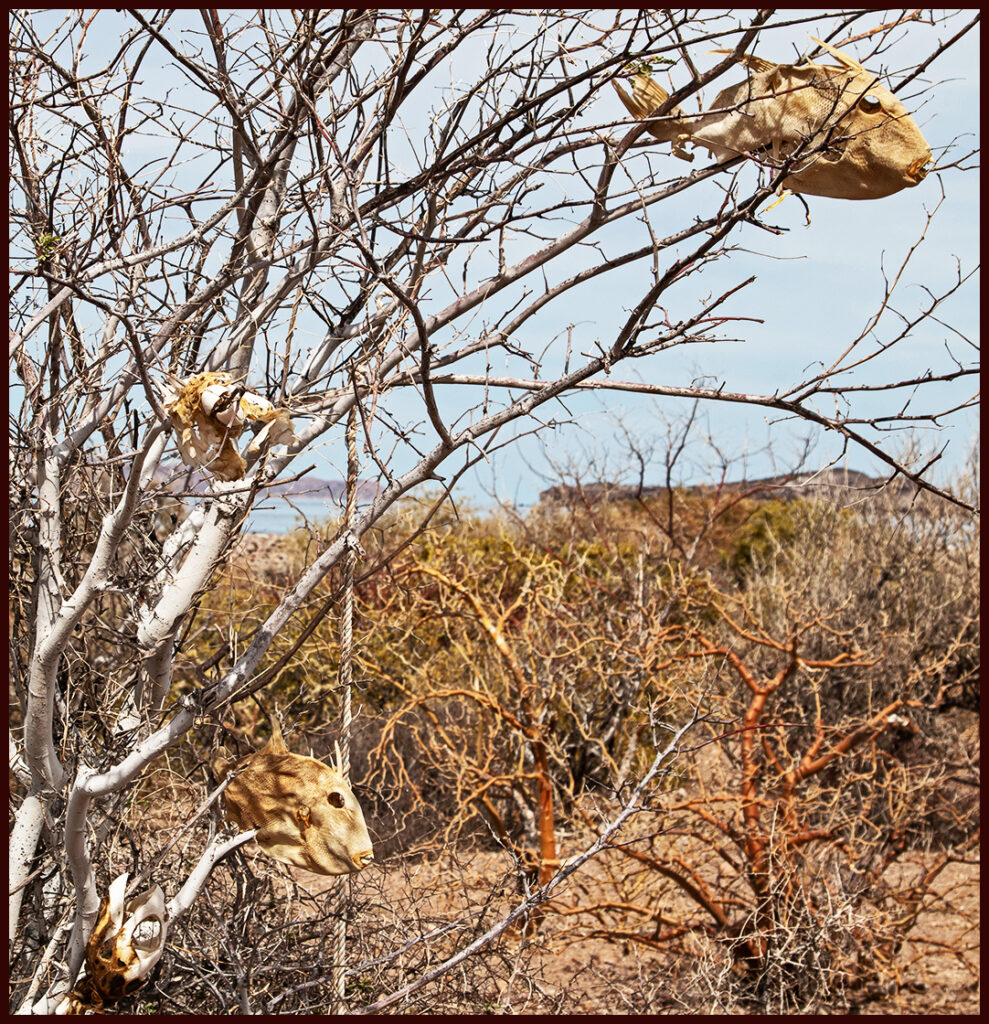

On the shore we found two of these beauties to add to the skeleton tree.

The tree with parrot fish, sea turtle and the new additions we determined were …

Titan trigger fish. (internet photo) There must be a reef nearby with all the coral chunks and reef fish skeletons found on the beach.

Alas, time’s a wastin’ so after the lovely sunrise we bid farewell to a pristine and rarely visited area.

Scene off the road to Puerto Agua Verde. Even in wet years, Baja is mostly desert.

Returning north we stop to camp before reaching San Ignacio. There is a paved road on the east side of Las Tres Virgenes (three virgins), a range comprised of 3 volcanoes. Many climbers come here, but unless you have some special dispensation, the road is closed beyond a small resort. To the south of the main road there is ample evidence that the volcanoes were active recently, in the geologic sense of the word. We drove a dirt road north on the western side of the range and found a lovely campsite in an abandoned gravel pit.

The range showing the Tres Virgenes volcanoes.

Lava fields stretch out from the highway.

View from our gravel pit.

Camp companion, a side-blotched lizard.

Volcanic evidence at our camp. The white ones are ashy tuff.

There were very few flowers in evidence, but there were a few scant blooms on a different sort of ocotillo plant. Perhaps these are what are keeping bees alive.

With the tiniest bit of spilled water, bees appeared by the dozens. There must have been a large hive nearby. I’m sure they were sad to see us go.

The town Guerrero Negro (black warrior) was founded in 1957 when Daniel Ludwig built a salt works there to supply the demand of salt in the western United States. His company (later sold) became the greatest salt mine in the world, with a production of seven million tons of salt per year shipped to countries around the world. Fortunately, the company is somewhat ecologically responsible and has preserved a large wetland filled with resident and migrating birds. The town also relies heavily on a thriving grey whale-watching industry. Around this soulless city, we found the only remarkable spring flower display of the trip.

Long-billed Curlews stalk the wetlands. It’s worth the trip out to see the many avian inhabitants.

Flowers sprout from sand.

View from the highway.

Now we enter uncharted territory (for us). We follow the Pacific coast north to see the highest point on the peninsula. Surprisingly, near the ocean, the hillsides are starkly arid. We tried to drive to a sea lion reserve to see the animals, but the 4WD road in was too intimidating. (Photo below is not of that dicey road.) Driving through Ensenada is something of a nightmare, but eventually we were on the paved road to the park.

Arid coastline.

The beaches are rocky and people were legally carrying out truckloads of beach gravel for landscaping projects.

The seas were gray and roiling the day we were there.

Baja’s highest peak is Picacho del Diablo at 3,096 m (10,157 ft).

The Parque Nacional Sierra de San Pedro Mártir was established 1974, the first national park on the whole peninsula. The park protects an area of 250 sq miles. The National Astronomical Observatory is located at an elevation of 9,280 ft. The astronomical complex was built in 1975. Unfortunately the road to the top is now blocked off. It’s said one can see both the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California from the top.

Leaving the plains on the way to the park…a few more flowers.

And higher we go, towards the park.

National Astronomical Observatory

Desert bighorn roam the mountains but we didn’t see any. Plants found nowhere else on the peninsula thrive here. Pine/oak forests cover the higher elevations. Birds winter here that we see in our mountains…chickadees, nuthatches, piñon jays, juncos, ravens, bluebirds, etc.

Snow in Baja is an unusual sight. Snow lingers at these elevations.

Jeffery pines, white fir and sugar pines are the conifers found on the granite outcroppings. The pungent pine smell is rare in Baja.

The nights are cold. It was 27 degrees in the morning. brrr.

Pine Squirrel, aka chickaree.

Western Bluebird spending its winter in the south.

Lots of coyotes roam the mountains. This cheeky fellow came right into camp.

A flower we recognize from Colorado, an Indian Paintbrush.

The San Diego Zoo has been breeding California condors for release since 1987. They still release a few captive juveniles every year in the park. We did see a condor soaring; too far away to get a photo. Because of the condors, certain portions of the park are closed to visitors.

We’d planned to spend another day in the northern section of Baja, but soon found ourselves in wine country. Thousands of acres near the border are devoted to vineyards, many producing grapes for American wineries. It’s all private so we continued to the border crossing at Tecate where we had our first encounter with the “Wall”. Tecate is the easiest and fastest crossing we’ve found.

Vineyards spread for miles and miles.

The funky old road has been replaced by a high speed highway.

The new wall at the Tecate border crossing.

Until next time, adios mis amigos.